About ten years ago, I was part of a founding team for a product way before its time (said like everyone with a failed start-up). A no-code solution that would allow small businesses to deploy simple mobile apps without any technical knowledge. It was a great idea with a great name, MadeApp, and it fizzled out quickly.

For a long time, I had a photo favourited on my phone from this time. It was a picture of my embattled laptop propped up on a cheap IKEA laptop stand on a cheap IKEA desk. On one side of the laptop was a pile of empty cigarette packets, on the other a leaning tower of empty Redbull cans.

It was a snapshot of the product’s first release being pushed to production the day before the trade show where we had committed to launching the product. As the only coder on the project, I battled through a couple of weeks, working almost 24/7 to finish the product and be ready for launch.

For a long time, I used this photo as a point for celebration, a marker that I, and I alone, had won this battle against the code. I had the grit, resilience, determination and strength to accomplish this.

And for a while, this was great motivation for me. If I could do this, I could do anything.

Turned out I couldn’t, but that’s a story for another time.

Individual Strength Industry.

I wasn’t the first to be caught up in this vision of individual strength being the core factor for success. There is an entire multi-billion dollar industry around this concept. Books, training courses, and consultants all help people build the grit and resilience to get through any challenge that their work and life through them.

Books like Grit and Mindset have become international best sellers on the topic. Compounded by the rise of “hustle culture”, this concept is big business.

But is it all that it’s cracked up to be? Bruce Daisley’s incredible Fortitude book covers this topic in great detail, but a couple of data points stand out.

- The science that the Grit book is founded on has come under significant scrutiny in scientific peer review. The paper “In a Representative Sample Grit Has a Negligible Effect on Educational and Economic Success Compared to Intelligence” probably gives quite a lot away about the content in just the title.

- The core study, where praising determination over skill or intelligence in groups of school children showed improved results, of the Mindset book was unreplicable when attempted 12 times by Edinburgh University in real classrooms.

- A colleague of the author of Grit, Martin Seligman, developed a resilience program for the US Army. The programme mainly focused on preparing soldiers for traumatic combat experience failed to show any measurable improvements in the rates of Post Traumatic Stress, or suicides, in Soldiers returning from combat.

Looking at this evidence, this industry is founded on some shaky science. OK, it’s easy to make counterarguments with a critical review, but I think we need to be careful about loading the expectation of success on the individual.

Mainly because it’s not how humans are designed.

Story Time.

I have a high level of empathy. Some people would classify me as an empath (however, I’m not keen on that term, as it suggests it’s some kind of gift, but it’s also a curse).

Being able to understand someone else’s emotional situation quickly causes me continuous pain and discomfort.

As I grew from a team leader to leading groups of much larger numbers of people, I really struggled with scaling empathy. I did, however, find a solution and I spoke about this at LeadDev London last year. I’ve also written about it on my blog.

When delivering a version of this talk with slides, I included the following slide.

The slide explains how the solution I had put in place created a network of support within the group.

It was a slide that I kept coming back to over and over again. It resonated with me. Over time I started to understand why. I had drawn out the real strength in the group, not the individuals, but the connections between them.

Social Strength

The more I started to think about this, the more research I did, the more it became clear that this strength made total sense. Humans are physically hard-wired and encoded, programmed even, to need social support from other humans.

- Scientific study strongly points towards the fact that the human brain reacts in the same way to social exclusion as it does to physical pain. Multiple Cyberball studies have shown that when people are in an MRI scanner, their brains light up similarly when the ball is no longer passed to them, as they do when experiencing physical pain.

- Sports teams with strong social bonds have been shown to have much higher pain tolerance than the same people when placed in other teams.

- Research on heart attack survivors showed that having a strong friends network was the most significant factor for recovery and reduced future complications. It was more important than quitting drinking, quitting smoking, or taking pharmaceutical drugs.

It’s pretty easy to read the science and conclude that strength comes not from the individual but from the social bonds in a group.

Model and Measure.

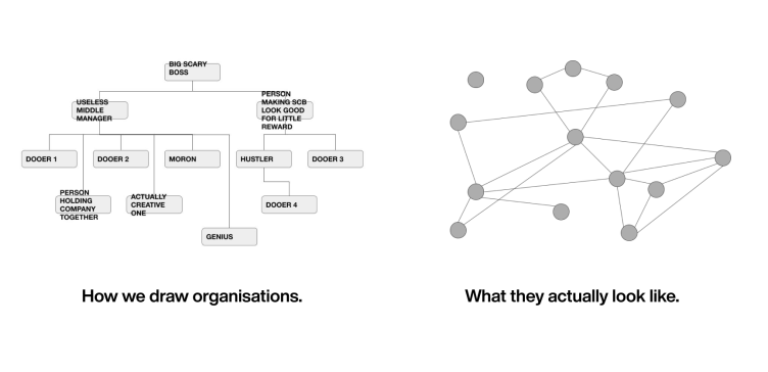

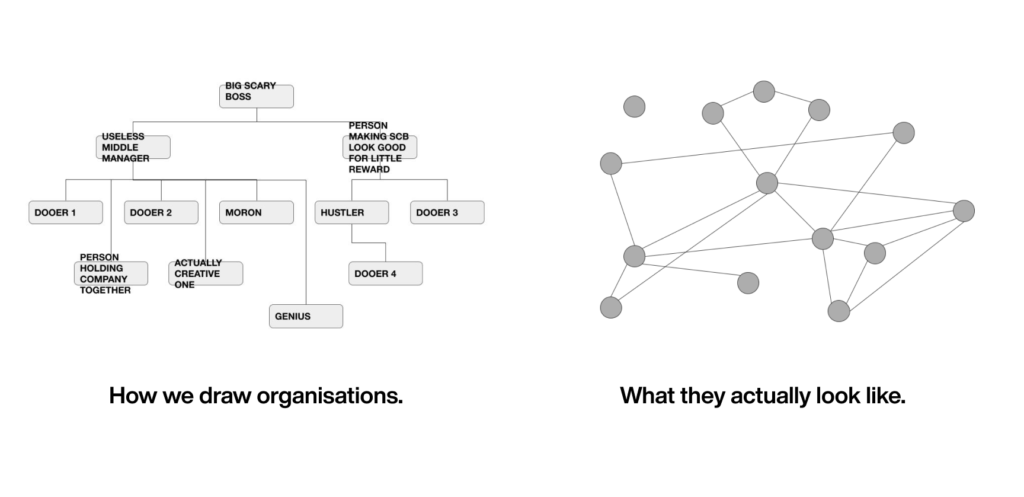

We draw organisations like the left, and we also measure their strength of them in the same hierarchical way. Engagement surveys, employee net promotor scores, and even team-related KPIs and OKRs are summed up through the hierarchy.

But, the strength in our organisation looks like the network on the right. In order to understand how strong we are as organisations, we need to model and measure like a network rather than a tree data structure.

Diamonds Vs Pencils

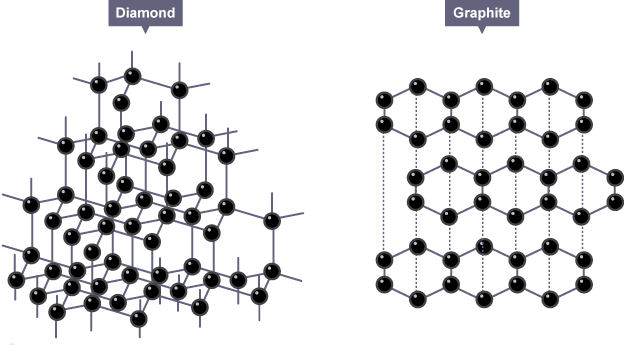

Diamonds and Graphite, the ‘lead’ in a pencil, are both carbon-based compounds.

However, the molecular structure is different in both. Graphite has loosely coupled collections of molecules, making it one of the softest compounds on Earth. However, a diamond’s crystalline structure means every molecule is supported by a connection to 5 other molecules, making it one of the most rigid compounds on Earth.

For a while now, companies have modelled themselves on Graphite to create dynamic organisational structures. The logic is sound. Small teams of tightly connected individuals loosely connected to the rest of the organisation reduced the dependencies between them, allowing a company to move faster.

However, in reality, this makes the structure incredibly brittle. If something impacts an organisation, or you need to make a significant organisational change, all of the separate units have to move in the same direction.

If you’ve set up a structure where teams can run independently, in somewhat independent directions. One of two things happen, you’re either fantastic at an alignment or lucky, and every team moves towards the direction change, or your teams move in different directions, and they snap like a pencil.

We benefit from modelling our organisation around a diamond of social connections.

- If everyone has a strong coupling to a number of other people, then they will perform better.

- Culture and values will spread more naturally, rather than silos of them building in separate teams.

- Change can actually be initiated more easily. Either the company is more closely aligned to the goals by ‘osmosis’, or you can influence change by convincing just a few influential nodes in the network, and the idea will spread, kind of like a positive virus, to the rest of the organisation.

Measuring Social Strength: Pith Scores

If we want to model our organisation’s strength as a network of connections, we need to be able to measure it. We can do this with something I like to call Pith scores.

Pith is defined as “the important or essential part” or something. We want to measure the essence of a team. Measuring a complex network of messy inter-human connections seems complicated, but it’s pretty easy.

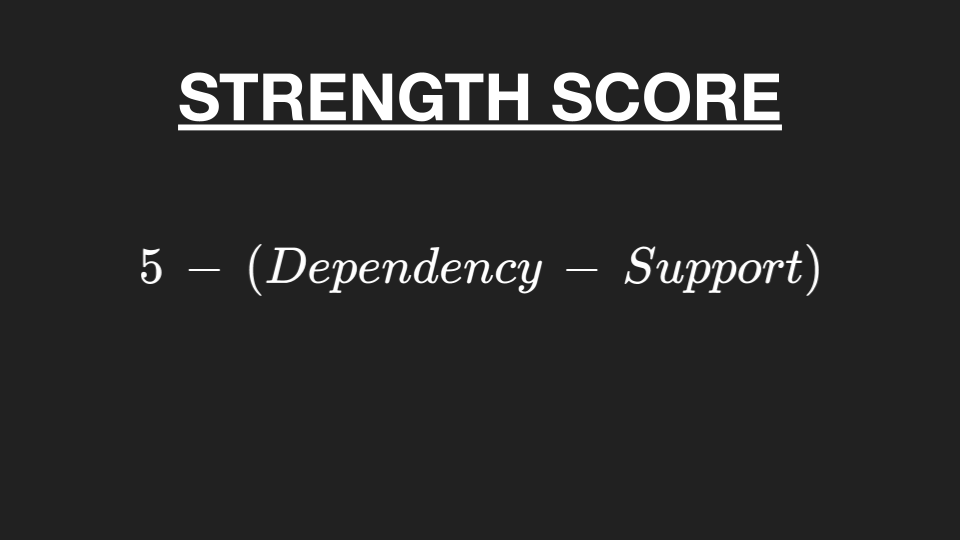

All you have to do is ask everyone to answer two questions about all the other people in their network.

- On a scale of 1-5, how much do you rely on this person?

- On a scale of 1-5, how well are they supporting this reliance?

With the answers to these questions, you can measure the strength of the end of each connection using the formula.

So the number is lower if there is a high dependency but low support. The number is higher if there is low dependency or the support needs meet the dependency. Easy!

You can then also work out the strength of the whole team/network, the “Pith Score”, using the following:

This might look complicated, but we’re just comparing the strengths of the current connections with the overall potential of the team and getting a percentage.

We now have a measurement of the team strength that we can take periodically to understand changes and the impact of any improvements we put in place.

Visualisation

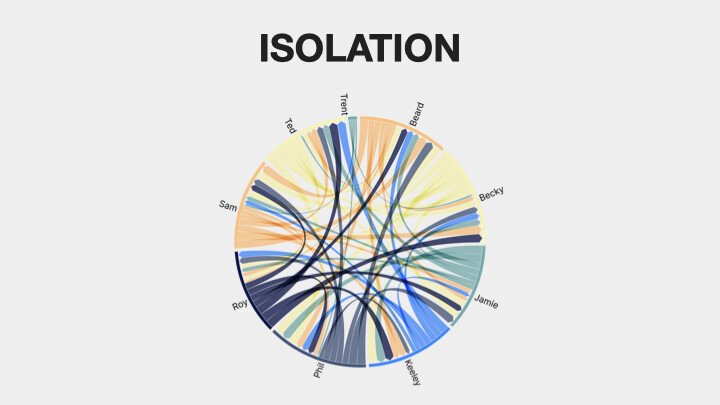

Now that we have measurements of the network, as well as creating an overall score, we can easily visualise what’s going on in the team.

Using Chord Graphs, you can plot the need, support, and even support gaps within a group of individuals.

Examples

I’ve been testing this idea with a few teams over the last couple of months, and it’s thrown up a couple of interesting examples in the visualisation that would have been harder to see without it.

Isolation.

In this graph of dependency, you can easily see Trent (names changed to protect the innocent) has a minimal dependency on the rest of the team. Trent was a Marketing specialist in a product team, happily plodding on with his work but had no specific involvement with the rest of the team other than joining some team ceremonies.

His problem space was tightly coupled with the team (he was doing product marketing for the product he was building). It initially made sense to put him closer to the team. However, moving him to a competence-specific team, even if it’s counter-intuitive, allowed him to flourish and support the product team much better.

Hidden Leads

In this example, you can see that most of the team has a dependency on Ted. You would make the assumption that Ted was the team lead in this situation. However, he wasn’t, at least on paper. The team lead wasn’t performing, and Ted silently took the slack.

Removing the underperforming lead and giving Ted the title he was performing anyway completely unlocked the performance of this team.

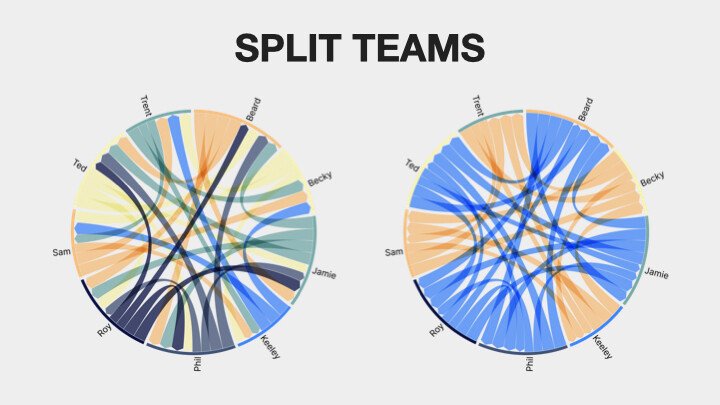

Team Splits

In this example, you can see two groups of people with dependencies on each other but zero cross-connection between the two groups.

In this situation, one of the groups was an operations team supporting an engineering team, but their work didn’t cross over.

After initially trying to connect the work of the two teams closer, it worked much better, splitting the two teams and giving the operations team the freedom to define their own goals.